Monument to Chico Mendes in Rio Branco

Monument to Chico Mendes in Rio BrancoHis murder placed the State of Acre at the center of world attention and Andrew Revkin's book, The Burning Season spread the story.

[NOTE: This post was linked to Andrew Revkin's DotEarth report The Uncertain Legacy of Chico Mendes. There's also a follow-up post about the critical issues of road and dam building in the region here.

Two years ago the Chico Mendes story was enshrined as a national legend through a 55-episode TV soap opera called “Amazônia: From Galvez to Chico Mendes” which I had the unique experience of watching from a Santo Daime community in Capixaba, not far from the Mendes home of Xapuri.

Before his death, Chico Mendes had organized the rubber tappers of Acre into a popular front called the Peoples of the Forest Movement that successfully reached out to international organizations for support and began the long process of changing forever the environmental politics of Brazil.

Today, Chico Mendes is not only memorialized through monuments, local parks, street names, posters, and T-shirts. Perhaps his greatest legacy is the sustainability movement of green government and large landscape eco-planning that has generated extractive reserves, National Parks, protected tribal lands, and multi-use zoning.

Throughout the first term of Brazil's President Luiz Ignácio Lula da Silva, the internationally famous Chico Mendes disciple Marina Silva was the Federal Minister of Environment. Innovative policies were advanced and today Brazil has some of the most ambitious environmental legislation in the world. But the map is not the territory. On the big issues like dams and roads, idealism has been generally trumped by the forces of development and, on smaller questions of implementing the goals and targets of ecologically sensitive land management, the politics of county elections often introduce "adjustments".

I got my first real dose of where things might be headed when I attended Expo Acre and witnessed "Country America" in Brazil.

It's clearly a different world from the days of Chico Mendes. Mangabeira Unger -- Minister of Strategic Planning and coordinator of Amazon development – observes that the question is no longer whether or not Amazônia will be developed but whether the development will occur in a chaotic or orderly fashion. President Lula states the politics in simple language, “The 20 million people of Amazônia want TVs and refrigerators too.” And the newly appointed Minister of Environment Carlos Minc points out that it is much easier to close an illegal sawmill than to replace the jobs that it had created.

In a world hungry for food and biofuels, Brazil is destined to be one of the greatest suppliers of biological energy. There are vast land areas that can be converted to agricultural production and a national infrastructure is being built to deliver commodities from the interior to the global market place. The big question is whether the new crop fields and pasture lands will trigger more deforestation or if they can be based on reclaiming and renewing degraded lands abandoned after earlier ravages. Unfortunately, burning and deforestation have been moving back toward dangerous levels.

Brazil has a national goal of achieving sustainability and a stated target of reducing deforestation by 70% across the next 10 years that has been met with a lot of skepticism. Acre is one the the great laboratories where we are likely to discover if the notion of sustainability is grand or grandiose. Is "sustainable development" really possible or just a green-washing oxymoron? Many are watching.

How does it look from my perch in this little place in the boonies called Capixaba? I'm only a recent visitor and I'm no expert on sustainability, nor on Amazônia. I cannot say that I grasp the enormous global forces of the 21st Century but I sure can feel them on the ground. My views are just impressions, idiosyncratic pictures rather than scientific data. Change, contrasts and contradictions seem to be everywhere in Capixaba.

There are beautiful views

and devastated landscapes

and vast open spaces.

There are working oxen

and heads of beef.

The main highway connects with a newly completed bridge to Peru, creating the first cross-continental route from the Rio de Janeiro, Brazil to Lima, Peru.

Now there are "caravans" of Land Rovers making the first "expeditions" even before the paving is complete.

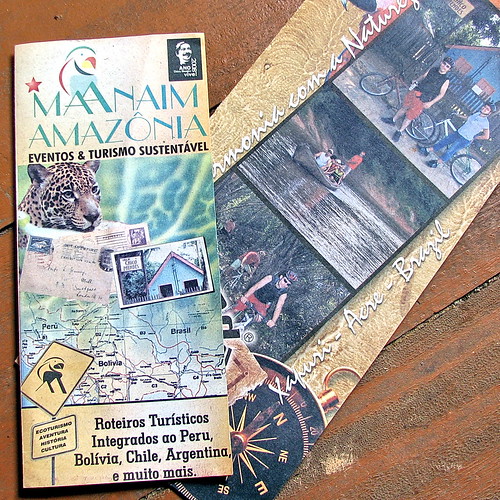

Brochures are promoting Road-to-the-Pacific tourism.

There are new hotels and 4x4 pickups

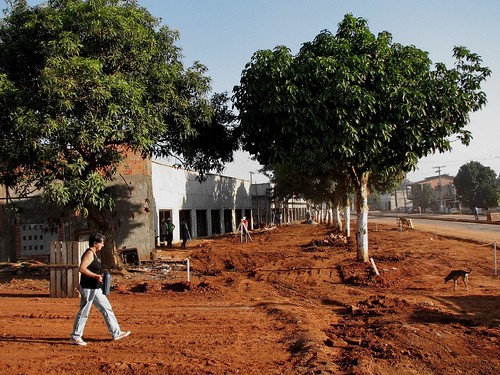

The little town of Capixaba is getting spruced up with its very first urban renewal project including a center-divided highway

its first sidewalks

and its first strip mall

The main industry of the town -- a sawmill and charcoal producer -- is responsible for most of the local deforestation. I'm told that the logging is legal and the finished lumber is mostly for export.

There are large grain trucks hauling commodities to processors.

A short distance from Capixaba there is the region's first ethanol plant

and miles of new sugarcane plantations to feed it.

Away from the towns and large ranches along the main highway there is now a mix of fragmented forest lands and smaller parcels that were acquired by people who arrived to settle in the area following the first big waves of deforestation and land-use conversion.

The Brazilian government has been encouraging settlement of the interior since the latter part of last century often under the slogan: "A land without people for people without land." The sub-divisions are called colônias and the settlers colônistas. These smaller land-holders may now be one of the keys to future land restoration and sustainability.

I have been living at such a colônia called Fortaleza -- a small family land holding and spiritual center where folks are very interested in healing the land. In honor of the 20th anniversary of the death of Chico Mendes some contemporary serringeiros brought large palm fronds across the river from Bolivia

traveling in a large canoe dug out of a single log

in order to restore the old serringeiro house that is maintained here as a monument to the peoples of the forest, past and present.

Recently, EMBRAPA -- Brazil's premier government agricultural research and extension service -- conducted an all-day ecological and reforestation workshop for area land owners.

It was a lesson in sustainability demonstrating how the land might serve multiple uses integrating agroforestry, small herds of animals, riparian restoration and reforestation into a land use plan.

The key to such a plan is fencing the ecological landscape for the separate uses. Unfortunately, at the end of the workshop when asked how the fencing materials would be paid for, they were only offered the opportunity for low interest bank loans. The land owners groaned and retired for coffee and cookies.

These small-holders, who have a real connection and love for their land, would like a better life both for nature and people. They do whatever they can with their limited resources. And, yes, they do want refrigerators and TVs as well.

Rural electrification arrived in this area only 2 years ago

Light for All

and now most of the simple houses also have satellite dishes and energy meters.

And, considering realities such as rural roads that often look like this

one can easily understand the desire for 4 wheel drive vehicles.

Last, week during a particularly stifling day of tropical heat and humidity, a friend asked what I was writing about. I answered, "Chico Mendes, environmental damage, energy and climate change." She responded, "Yes, it's been getting much hotter here. Air conditioning is becoming seen as a necessity in Acre." As the beads of sweat rolled down my face I said, "I understand."

No, I don't believe that I want air-conditioning and I have little interest in TV but after slogging down a muddy road to catch a ride on the delivery truck and spending 14 hours to get 4 hours on-line at the LAN House in Capixaba, I really want a home Internet connection. Everyone has their necessities. I wonder how they can be met?

My knowledge base is from Oregon where everyone has these necessities -- and more! And, it provides a model for Acre.

Oregon chainsaw parts in Capixaba, Acre.

Back in Oregon, USA we struggled long and hard to save the forest. There were some small victories -- postage stamp size parcels of protection and some better practices. But, even with only less than 10% of the primary forest left, the local sawmill is still cutting old-growth trees. It's obvious how local necessities were met. They were extracted from the forest.

Why won't it be the same here in Acre? Why won't Brazil follow the American model of achieving prosperity and good things through unsustainable extraction of the resources of nature? If it is to be different here, where there is still so much left to protect, how will it be paid for?

Long ago the American naturalist and founder of the Wilderness Society Aldo Leopold said, "We abuse the land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect."

Today population growth, peak energy, climate change and more are forcing us all in to an awareness that all beings are connected in a planet-wide community. Global warming and sustainability issues are forcing us toward a new ways of thinking. Might agriculture and forestry provide the tools needed for the conservation of people and nature?

There are now serious discussions about how emerging carbon markets might provide payments for carbon sequestration in forests through avoided deforestation and in soils through biochar. Indeed, there is the possibility that sequestered carbon may become one of the world's most precious trade-able commodities and a significant source of conservation-oriented work for rural people which would be a great boon for both people and nture..

But trading is a tricky business favoring large corporate and institutional players over smaller stake holders and, as recent events demonstrate, markets are frighteningly susceptible to fraud and manipulation. Can they be regulated to give indigenous peoples, small family farmers and ranchers, and the people who live simpler lifestyles a real role in protecting the land?

There are still a lot of these folks on our increasingly urbanized planet and they are the land's most immediate caretakers. They would love to be paid for providing the services that are needed by all. Indeed, these people of the land and the forest -- the people of the vision of Chico Mendes -- may be the key to our collective survival.

Lou, this is a beautiful essay that dives straight to the heart of the human dilemma and all the issues of justice and survival we face. Thank you for inserting yourself in that place - the physical, mental and heartspace as well.

ReplyDeleteUltimately, don't you think that we must grapple with the issue of growth? If we could only stop the growth in our numbers we might have a prayer of meeting everyone's needs. But as long as births exceed deaths, we will never catch up. What is being done in Brazil to help women choose smaller families?

Hi Kelpie,

ReplyDeleteI'm no expert on womens's issues in Brazil but my impression is that the current governing regime has certainly advanced the options of choice. Basically, I see the worldwide pattern here -- urbanization reduces family size and the new smaller families are larger per person consumers (like getting a new car or great vacation rather than a new child). So the question becomes "how many children at what level of consumption?"