Save the planet – a message from another world

The first member of a remote Colombian tribe ever to set foot in Britain brings a stark ecological warning

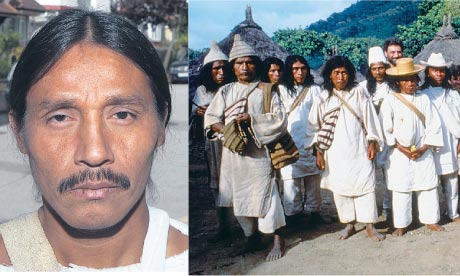

Jacinto Zabareta in north London and members of the Kogi people in Colombia.

Photograph: Guardian

Via Guardian

By Patrick Barkham

Jacinto Zarabata sits in a suburban back garden in north London and unselfconsciously uses a stick to probe the inside of a gourd, which is shaped like a rather phallic mushroom with a bright yellow cap. The first member of the Kogi people of Colombia ever to visit Britain is wearing traditional rough cotton clothes and has a cloth bag slung over each shoulder as he chews toasted coca leaves.

It would be easy to view Jacinto as a noble savage; an exotic being from a pristine indigenous culture still living in impenetrable pockets of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, the highest coastal mountain range in the world. But this small, self-assured spokesman for the Kogi soon subverts that stereotype. As he answers my first question in fluent Spanish, he delves into one bag, extracts a camera and takes a photograph of me.

Jacinto has made the journey to Britain because the Kogi have embarked on an unusual and ambitious mission. They are making a movie about their way of life – but not for themselves, as part of some kind of do-gooding community workshop; it is for us, and it carries an uncompromising message. One of very few indigenous American people to resist the ravages of Spanish conquistadors, Christian missionaries and, now, eco-tourists, militias, drug lords and heavy industry, the Kogi have observed frightening changes to their homeland in recent decades. The glaciers are melting, storms have increased in ferocity, there are landslides and floods, followed by droughts and deforestation. The Kogi, who live by a complex set of spiritual beliefs, are the "elder brother" and guardians of this, the heart of the earth, and they believe we in the west ("little brother") are destroying the planet. They have come to warn us, before it is too late.

Jacinto, who is a spokesperson for the Mamos, the Kogi spiritual leaders who have a unique wisdom forged by an entire childhood spent living in the dark, arrived in London the previous night. He is staying with Alan Ereira, who made a BBC documentary, The Heart of the World, about their life 20 years ago. What are Jacinto's first impressions of our society?

"The first thing that is noticeable to me is that this is still the world," he says. "What's visible is construction, what you have made. This is not something we, the Kogi, are used to seeing. You give precedence to the use of a thing rather than its source. That's the intellectual error. Ultimately, it's all nature." From Jacinto's viewpoint, when we glance at a car we might assess its cost and the status conferred on its driver. We don't recognise it as a clever piece of engineering of resources that once lay inside the earth.

The Kogi are witnessing some of this extraction first hand. Coal mining in the Sierra Nevada has boomed in recent decades (fuelled in part by the demand for cheap foreign coal in post-miners' strike Britain). Over centuries, they survived the wars waged on them by retreating further into the mountains, through dense rainforest and cloud forest dubbed "El Infierno" by settlers. There are still no roads to the Kogi's traditional settlements (Jacinto's home does not exist on official maps), but global capitalism is slowly conquering the Kogi's isolation.

Not that Jacinto does not embrace victimhood. He highlights the positive developments for their culture. When Ereira's film was broadcast around the world in 1990, there were 12,000 Kogi. Now there are 18,000. After centuries witnessing their lands being plundered, they have been returned significant traditional areas and sacred sites by the Colombian government. Last month Juan Manuel Santos, the country's new president, visited the Kogi to be blessed by the Mamos before his official inauguration. "In a sense, the Kogi are trying to take over the Colombian government and build a sense of responsibility into the president himself," says Ereira. "The Kogi are saying, 'How are we going to sort the world out?' They must be the most proactive indigenous people on earth."

In Ereira's documentary, the Kogi's message was ahead of its time: they warned of climate change, and that "little brother's" (the west's) hunger for energy and material possessions was "cutting out of the eyes and ears" of the great mother (the earth). But we didn't listen. And so, 18 months ago, Ereira received a phone call out of the blue from the Kogi (Spanish-speakers such as Jacinto use mobile phones when they visit westernised cities; there is little reception in the mountains), demanding his immediate presence. Ereira thenreturned to the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, trekking on a mule through the rainforest. He was taken to sacred sites he had never been allowed to visit before and the Kogi, some of whom had received training with video cameras and broadcast a series of seven-minute documentaries on Colombian television, explained their new film-making mission.

When Ereira returned, he found the Kogi's heartland remarkably unchanged. "You don't see the transformation you see in Amazonian traditional societies, where you have an impoverished western urban culture in indigenous villages. You don't see the T-shirts and baseball caps. The Kogi's identification with their culture is phenomenally strong. The belief of the Mamos in their responsibility for taking care of the world is absolute, and it's the duty and function of the rest of their society to ensure they do that. That's not broken down."

But it has been changed by the growing relationship between the indigenous community and the government. Increasingly, a few salaried Kogi who speak Spanish and work as local officials have the power to get things done. Ereira wonders if this will undermine the traditional authority of the Mamos – and if the Kogi's unique way of thinking is at risk. "It's a perception of reality which is contained in their language and is utterly different from ours. My fear is that the moment you mess with it in any way, it's lost. You probably can't hold that experience if you speak Spanish because the conceptual world is totally different. You're at risk of losing this last trace, this philosophical reserve."

Jacinto, however, does not fear for the future of Kogi culture. "There has always been an attempt to bring other ideas and thoughts into our way of life," he says. Doesn't he worry that the Kogi will be drawn to the bright lights of westernised cities, such as nearby Santa Marta? "No," he says. "The Mamos have authority over people. People can experience other cultures but they have an obligation to return. If they don't, the authorities are obliged to go down [the mountain] and get them." Doesn't Jacinto crave cars, houses and restaurants? "At this particular moment there isn't that need," he says, gravely. "But I can envisage a time when we may adopt certain things."

One thing they have adopted is filmmaking – the Kogi believe a movie is their best hope not only of telling little brother where he is going wrong, but showing him. This time, however, the Kogi's film is not being masterminded by Ereira: "They decided after the first film that this was the best way to connect with the world," he explains. "But they realised that to be in our hands was just not a good idea." So Ereira is assisting, and seeking funding for the project, which will be completed next summer. Judging by the Kogi's trailer, the authentic voice of an indigenous people makes for compelling viewing but the BBC have not expressed an interest, so instead, Ereira and the Kogi are planning a movie release. Footage of the Kogi conducting rituals beneath a spectacular tree is straight out of Avatar. "Avatar has done great work for this," Ereira says. "Twenty years ago, the Kogi were pushing on a wheel that had just started to turn. Now that wheel is really rolling and they are part of the zeitgeist."

The Kogi may not feel under attack culturally, but in their mountain environment "a lot has changed" in the last two decades, according to Jacinto. "The Sierra is the heart of the world. It functions the same way as our own heart does – it sustains the organism," he says. "There has been snow melt, landslides and earthquakes. People are damaging the sacred places from where the damage can be restored."

Why is little brother so greedy? Jacinto chuckles and rubs his gourd, a sign he is thinking. (The mushroom shaped cap on the gourd, which men carry to symbolise their connection with the womb, is a sign of his accumulated thought.) "Habit," he says, finally. "That ambition to have more doesn't have a framework. It's just a drive to accumulate. The habit is a competitive one. 'What everyone else has I must have too, otherwise everyone else has power over me.' The consequences are evident, but it doesn't seem obvious to you," Jacinto says. "You can go and live in space, that's fine, but you don't seem to be able to go back to the understanding of how to live harmoniously with the earth. That's something you've forgotten."

Yet the Kogi hope we can still reconnect, by seeing the value they place on thinking and their spiritual world. "When you understand that, you begin to understand yourself a bit more," Jacinto says. "Originally, the great mama brought us into being so we would be guardians of nature. You, the little brother, was given this knowledge of how to treat the earth and the water and the air. At some point there was divergence and you, the little brother, went on a different path.

"We, by example, don't live like you do. You come to the Sierra, there are no factories, there is no industrial agriculture. Now we really want you to look at the images of how we live."

No comments:

Post a Comment