"D" is for Dilma's Decision, Deforestation, Development, Dams and Drought

Dilma Rousseff, President of Brazil

Tomorrow, 25 May 2012, is the deadline for Brazil's President Dilma Rousseff to decide whether to accept or veto (in whole or part) the devastating new national Forest Code that was passed recently by the Brazilian Congress.

Andrew Revkin of the NY Times blog Dot Earth suggested that I might submit a "Postcard From Acre" describing the view from my perch in Brazil's western-most Amazonian state which borders on Bolivia and Peru.

Andy said, "You can keep it short, Lou -- just a quick review of what's been happening with Brazil's dream of development, the new Forest Code and some good links." I thought, "Right, a short review of the complex choices that now face Brazil -- choices with enormous domestic and global ecological and economic implications! Ha! It would be more like a tome than a postcard."

That was two weeks ago and I've been fussing over it ever since and asking, "what is the bottom-line organizing theme that might allow a thoughtful layperson (I'm not a scientist) to relate to an issue of such complexity?" As my mind swirled through the complications, confusions and controversies, I kept arriving at one simple thought, IT'S ALL ABOUT WATER.

But how can water possibly be a problem in the world's largest rainforest -- the Amazon basin that receives 20 percent of the world's over-land rainfall, that drains, via over 100 tributaries larger than the Mississippi, an amazing 17 billion metric tons of water into the ocean each year?

Let me explain.

Below is a bag of Atlantic water vapor that was gathered in Rio Branco, Acre -- 3,000 kilometers away from Brazil's east coast -- during a teaching demonstration that was given to me 2 years ago by Foster Brown who is a Federal University of Acre ecology professor and Woods Hole Research Center Senior Scientist .

In a process called evapotranspiration, water vapor is released into the air by the vegetation of the Amazon forest which supplies about three-quarters of its own rainfall. David Campbell tells the Amazon water-cycle story gloriously in his book, "A Land of Ghosts":

Even though we are only about600 kilometers from the Pacific Ocean [in western Acre], most of the air and clouds overhead originated on the other side of the continent in the Atlantic trade winds. During the journey from the Atlantic to the Andes, water vapor is repeatedly absorbed and recycled by the vegetation. In fact, the typical Amazon forest returns roughly half of its own rainfall to the sky through evapotranspiration. Rainwater is absorbed by the roots, transported in the vascular tissue of trees, shunted through the metabolic pathways of plants, utilized in various physiological processes, and eventually released back into the atmosphere through the leaves. Another quarter of the rainfall evaporates from the surfaces of trunks, branches, leaves, and other components of vegetation. Only a quarter of the rain is carried away by the rivers. The forest, therefore, creates about three-quarters of the moist climate on which it depends. The forest and the air above it are an integrated system.

...

How do I know I am breathing Atlantic vapor? After all, the raindrops here look the same as any others. The raindrops carry the secret [isotopic] information of their source, and the discovery of this fact, by Eneas Salati and his colleagues at the National Amazon Research Institute, was one of the greatest but least celebrated insights of twentieth-century science.

...

The startling result was that by the time the atmospheric water vapor reached Manaus, 1,500 kilometers from the Atlantic, it had been recycled as many as fifteen times; by the time it reached Benjamin Constant, about thirty times. Each passage takes about five and a half days; therefore, the water vapor that I am breathing today on the Rio Moa [in Acre] blew in from the Atlantic five or six months ago and has been incorporated into the very substance of this vast forest.

In this manner, the westward passage of the atmospheric water vapor is slowed down and the capacity of the land and its mantle of vegetation is greatly enhanced. If the forest is cut down, rainfall will decrease substantially, not only over the Amazon itself but also in areas to the south, including Brazil’s grain-belt states of São Paulo, Paraná, Santa Catarina, and Rio Grande do Sul, where seasonal winds shunt Amazonian water vapor. When first published in the mid-1980s, this information created a stir in agricultural and economic sectors of Brazil, because it showed for the first time that Amazonian deforestation could decrease agricultural production hundreds of kilometers to the south. For the first time the consequences of Amazonian deforestation on the pocketbook of the nation was clear.More recently scientists have discovered a "River in the Sky". The evapotranspiration of the 600 billion trees of the Amazon basin functioning as geysers results in sending 20 billion metric tons of moisture up into the sky annually. That's 3 billion metric tons more than the rivers drain into the Atlantic and the upward flow of energy is so powerful that it sucks moisture inland from over the Atlantic and charges the easterly flow of wind. Below is the powerful TEDx presentation by the Brazilian climate scientist Antônio Nobre explaining, with a spirit as strong as the science, how it works.

[note: to see the translation subtitles, start the video and watch for the red CC button at the lower right of the player frame. Clicking on it gives a choice of English, Portuguese or Spanish subtitles.]

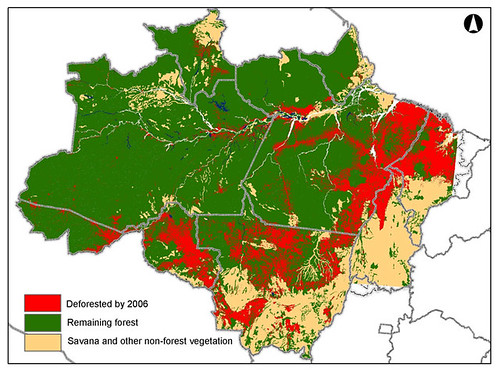

Sadly, this science has had great difficulty making it's way effectively into forest management policy, local on-the-ground practice and law enforcement. Indeed, the forces of expanding crop and beef production were able to act for many years with impunity. By 2006, 20 years after Salati's pioneering research, the deforestation was surging and map of Amazonia looked like this:

Arc of Amazon Deforestation Brazil - source: Ecolgy and Society

Scientists are seriously concerned about what will happen as several stress factors combine into a feedback loop. A special report from the New Phytologist concluded that, "although mass die-off is not inevitable, ... when expected feedbacks between vegetation and climate are combined with fire incidence and land-use change scenarios, we conclude that Amazon rain forests are highly vulnerable to loss during the coming decades."

There seemed to be a hopeful change during the Lula Administration (2003-2011) as Environmental Minister Marina Silva and her colleagues put in place a new policy architecture of protected areas and sustainable development, and her successor Carlos Minc instituted a "shock-and-awe" campaign of aggressive enforcement of the Forest Code which resulted in -- along with mega-economic trends such as the 2008 economic crash -- dramatically reduced rates of new deforestation.

But it also triggered a push-back from the "ruralistas" (the farm bloc in Congress) and their allies among the more unscrupulous developmentalists who were not offended by laws that were not enforced. When faced with the prospect of having to compensate for past illegal actions and stiff enforcement, they demanded the amnesty and generally weakened regulations which now threaten to unravel the progress that Brazil has achieved in recent years. (The environment group WWF lists the negative features of the new forest code here.)

The changed forest law is not only opposed by the usual assortment of environmentalists and social activists. The NY Time's Simon Romero reports that President Dilma is facing a Forest Code decision, on the eve of the UN's World Sustainability Conference RIO+20, that will probably be for Brazil a defining moment:

Prominent voices in Brazil ... have weighed in against the new Forest Code, including the Brazilian Academy of Sciences and the Brazilian Society for the Advancement of Science, two of the country’s leading scientific groups. Anger over the bill has spread into popular culture. Exemplifying the sentiment in the entertainment industry, the actress Camila Pitanga broke protocol at an event here this month, calling on Ms. Rousseff, who was present, to veto the bill. Video images of Ms. Pitanga’s statement spread quickly on social media throughout Brazil. Stunning some of the ruralistas, support for a veto has also emerged among some corporate leaders in São Paulo, Brazil’s business capital. Valor Econômico, the country’s top financial newspaper, likened the moment to the battle over President Obama’s sweeping health care law, calling Ms. Rousseff’s choice “one of those decisions which define a government.” “This bill leaves Brazil in the Middle Ages,” said Paulo Nigro, president of Tetra Pak Brasil, a food packaging and processing company, who was one of several prominent São Paulo business leaders quoted by Valor voicing their opposition to the Forest Code.The Forest Code is not the only challenge. The leading Amazon researcher Philip Fearnside -- author of over 450 publications and identified in 2006 by Thompson-ISI as the world’s second most-cited scientist on the subject of global warming -- has an excellent analysis of the many threats to the forests of Amazonia. Nowadays, making the threats much worse, is Brazil's quest for energy to support its expanding economy and its massive rush toward large hydroelectric projects. Thus, water appears again as a central issue.

The Amazon Basin is being targeted for large hydroelectric projects. See full map database.

In a recent op-ed, Fearnside says:

The Brazilian government has launched an unprecedented drive to dam the Amazon’s tributaries, and Belo Monte is the spearhead for its efforts. Brazil’s 2011-2020 energy-expansion plan [pushed into place by Dilma Rousseff when she was cabinet chief in the Lula Administration - ed] calls for building 48 additional large dams, of which 30 would be in the country’s Legal Amazon region. Building 30 dams in 10 years means an average rate of one dam every four months in Brazilian Amazonia through 2020. Of course, the clock doesn’t stop in 2020, and the total number of planned dams in Brazilian Amazonia exceeds 60.Simon Romero of the NY Times recently reported the violent labor unrest and the dismal general scene at the building site of the large Jirau Dam on the Madeira River in Acre's neighboring state Rondonia. The article and accompanying video are a must read-and-view. And, here is a powerful set of NASA satellite images showing how a decade of road-building (before dams) has already impacted the forests of Rondonia. (The area of view is about 500 km wide.)

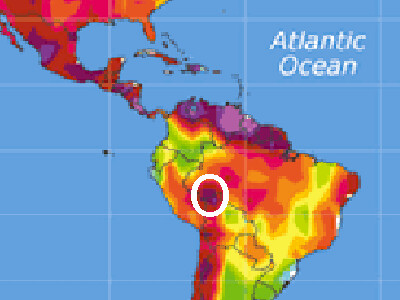

The future of the forests of my adopted Acre home now looks frighteningly problematic. Here's a computer graphic for mid-21st-century where Acre is shown as the epicenter of projected intensified Amazon basin drought according to the modeling of Aiguo Dai of the National Center for Atmospheric Research:

Image source: Climate Progress Darker red means more intense drought and the white circle is around Acre.

However, long-term computer model projections are known to be quite variable for a specific region so, I asked Foster Brown who said, "Well, crystal ball gazing like this is incredibly uncertain but we do know that Acre was the epicenter of the record-setting Amazonian droughts of 2005 and 2010. Maybe the problems have already begun"

This past year record-setting extremes have been seen in Acre. Below, are photos of the Acre River with a very low water level in August 2011 and near-record flooding six months later, in February, 2012 which conforms with the climate science predictions of more frequent and more intense extreme events.

Low water in the Acre River at Rio Branco (August 23, 2011)

Flooding in Rio Branco (February 22, 2012) -- photo by Sérgio Vale

Although Acre is still blessed with about 80+ percent forest cover statewide, the eastern portion of the state has already been hit with a lot of deforestation.

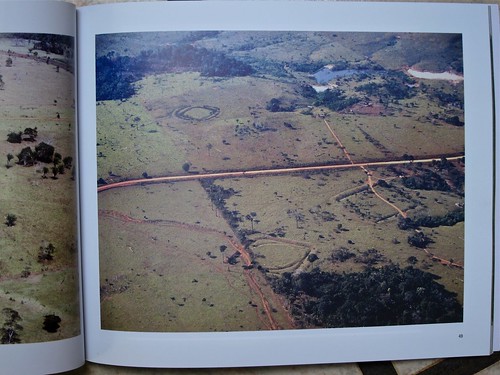

One result of the deforestation has been the discovery of around 300 geoglyphs or mound-like geometric land-carvings that date to the pre-Columbian Indians who are now thought to have occupied with large populations many areas of Amazonia.

Geoglyphs in Acre.

Inspection of these sites in Acre and Bolivia strongly suggests that much of the region was cerrado grassland as recently as 600 years ago. But, following the massive Indian die-off due to the introduction of the European diseases, large-scale agricultural impacts vanished and the forest returned. Indeed, across the long timeline, whole sections of the Amazon basin may have transitioned back and forth between grassland and forest.

[UPDATE: 19 June 2012 -- a new scientific paper published in Science presents convincing data that large pre-Columbian populations were concentrated in the East and Central Amazon and were small and shifting in the West. Therefore, it is highly unlikely that Indian agriculture deforested Eastern Acre. It is more likely that climate change created a cerrado at an earlier point and a return to forest when the earth was cooled (the little Ice Age) by volcanic eruptions. Since these eruptions overlapped the period of plagues that wiped out the indigenous populations, it seems more likely that climate change triggered a return of the forest. This important data is highly relevant to the astute comment by Ishmael Angelo (below).]

[UPDATE #2: 15 July 2012 -- The paper cited above has touched off a serious academic challenge concerning the impacts of pre-Columbian Amazonian populations and leading researchers are doubting it's conclusion of low populations in the western Amazon.]

Since human populations survive in both forest and savanna settings, does it matter which way Amazonia swings? I guess it depends on whether or not one wants to maintain the forest as a vast storehouse of carbon and hedge against global warming; as home for an incredible number of plant and animal species; and as a biotic pump that draws rain inland for Brazilian agriculture which feeds many people in the world.

IT'S ALL ABOUT WATER.

Pre-Columbian Indians who lived in savannas on the outskirts of the rainforest could not have had the same type of impact as the industrialist of today.

ReplyDeleteI think to equivocate their agricultural practices with today's industrial agriculture, beef production, and population growth, is misleading and somewhat validates that deforestation for the sake of agriculture is acceptable.

None the less, no matter the outcome, earth mandates checks and balances as with the floods and droughts. If we do not learn now, we will learn sooner or later.

The question is how far out of balance must we become before it is obvious, and a top priority for government and business and citizens, to develop and live sustainably in order to protect our life support systems.

Lou, thank you for your research and your work. I enjoyed reading and will share.

Hey Ishmael -- I'm super glad that you raised a question about the about the impact of the pre-Columbian peoples. I, also, was sort of shocked when I got into some of the current research. The recent scientific speculation is covered in the article that I linked:

ReplyDeleteOne result of the deforestation has been the discovery of around 300 geoglyphs or mound-like geometric land-carvings that date to the pre-Columbian Indians who are now thought to have occupied with large populations many areas of Amazonia.

So historically people have both denuded the forest and benefited from its water. Perhaps its just a political decision for Brazil.

ReplyDeleteJohn - Historically, the pre-Columbians were not trying to send beef to Europe, soy to China, ethanol to São Paulo, or wrestling with global warming.

ReplyDeleteThey were living in balance with the water resources and climate they had. Also, we can not say that they that they denuded the forest. The shift to grassland might have occurred due to earlier climate shifts.

What we can say is that many practiced a very interesting slash-and-char or terra preta agriculture that is the basis for the modern research into biochar for soil restoration, more crop productivity and a host of benefits. Here is a very interesting BBC video about it: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qqp_H95wjPE