I recently returned to the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais where I had a wonderful reunion with Baiano. Here is the full story...

I've been traveling recently with the Luiz Mendes family as they were presenting spiritual works in the State of Minas Gerais and in the greater São Paulo area during February and early March, 2007. There were many wonderful adventures which will I'll report in a series of upcoming posts.

Here, I'd like to begin by connecting with last year when I first visited the farm land of Débora and Eduardo Gabrish and their annual festival at the Santo Daime center of Flor do Ceu. At that time the biggest unexpected treat for me came not in the truly wonderful ceremonies but in the barnyard where I met Baiano early one morning, and every morning after that.

It all began because I’m an early riser. One day I wondered who was playing the radio full blast at the crack of dawn and I wandered down to the barnyard, sloshed through the cow shit and found Baiano getting ready to milk a cow.

He looked at me, called out “café?” and signaled over to a wooden crate with a thermos and a cup sitting on it. That’s how it started.

I don’t know exactly how Baiano and I communicated. He knows no English and my Portuguese is somewhere between tiny and minuscule. But using a few simple words and lots of gestures we surely did. Mainly, it was a “feel thing.” And once it started happening I even began to “understand” the DJ on the Brazilian country music radio station. One day I told Baiano about a curious twist in translating between Portuguese and English: The words, “ai, ai” in Portuguese mean “oi, oi” in English. But “oi, oi” in Portugese means “hi, hi” in English. So it’s, “ai, ai, oi, oi, hi, hi.” Baiano loved it and “ai, ai, oi, oi, hi, hi” became our special greeting that he would call out across the yard when he saw me.

Baiano loves to celebrate and share his simple life. He would say, “Look at all of this. I have everything -- a good wife and family and good work.

I don’t smoke or drink. I’m 62 years old and by the Grace of God I’m strong like the bull.” Then he would gesture sweeping his hand across the barnyard and say, “See, I have everything that I need and I can even give some away.” Debora says that Baiano often helps out others with free food and that he is known across the region as a natural healer of animals which is very important in a rural economy where few farmers can afford the services of a veterinarian.

I’ll never forget the day that I riled the bull.

We were walking out of the yard after the milking, on our way up to the kitchen for more coffee. Baiano pointed out a cow that was very, very pregnant. I moved closer to her which upset the bull. I really didn’t notice it but it was obvious that something was wrong when Baiano and Maria both snapped into high alert. Baiano went directly to the bull talking firmly but softly, “It’s OK. He is a friend. He’s a friend. It’s OK ….” He began stroking the bull’s balls and speaking more and more softly until the bull was completely calm. Then he smiled at Maria and me and beckoned, “Café.” No big deal, just something that happened while passing through the barnyard.

Baiano doesn’t drink Daime. He asked if I did and I said, yes. He responded by twisting up his face as if to say, “that stuff tastes awful.” But Debóra tells me that when one of the cows gets sick he goes to Eduardo and asks for a dose of Daime for it. The cow drinks it and heals and the family says that the milk and cheese carry the essence of Daime for awhile after that. Well, Baiano doesn’t drink Daime but maybe he eats it.

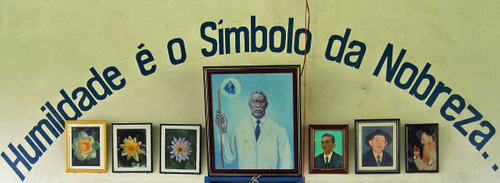

Or, perhaps Baiano is already so in the consciousness of Daime that it really doesn’t matter. In the Luiz Mendes line of the Santo Daime tradition it is said that “humility is the symbol of nobility.”

I don’t think this means kowtowing to authority or self depreciation but rather -- as in the Greek root word, humus -- being well-grounded and close to nature. In this sense Baiano is a true prince. So it wasn’t surprising at all to see, at the wedding of Debora and Eduardo, that it was Baiano who escorted the bride down the aisle.

The next day Baiano slaughtered a young cow that was clearly suffering with some kind of serious skin problem that I guess he couldn’t cure. Since its meat was healthy this was the animal that was chosen for the post wedding barbecue and feast. Killing it seemed like a gift all the way around.

A few days later Maria cooked buchada, a kind of a jambalaya made with the stomach lining of a cow. I thought about what I was eating and recalled the advice given by Ram Dass’s guru -- “don’t eat poisons and always eat food that has been prepared with love.”

It tasted pretty good.

I would eat any food that Baiano and Maria offered to share. Mostly, that meant a breakfast of good strong Brazilian coffee, bread and cheese. The State of Minas Gerais is famous for its cheeses, especially queijo minas frescal which is the popular local fresh farm cheese. One morning Baiano showed me how he made frescal.

Then he made string cheese from mozzarella. He cut thin slices from a big slab of mozzarella which he put into very hot water.

After it sat for a short while, he kneaded it back into a large ball which he then squeezed and stretched into long cords.

Finally, he cut lengths of these cords and fashioned them into beautiful braids of string cheese that we often ate fried with fresh baked bread.

Starting my days with Baiano and the animals was a profound experience. There, in his barnyard with its raw proximity to nature, I felt the deep meaning of his simple words, “Graças a Deus, eu tenho tudo.” Thanks to God, I have everything.

A bucket of milk

and feed for the cows.

Things were mostly the same as when I last saw him -- full of doing typical farm chores like milking the cows,

mending fences,

gathering and grinding up freshly cut cane for feed,

shoveling manure,

and packing up cheese.

There were new calves

that were receiving inoculations.

Baiano is quite skilled in doctoring animals and he was treating a sick

cow that was not giving good milk.

One morning I took mug shots of a bunch of his cows.

When I showed these images to Baiano in the tiny monitor of my camera, he immediately called out the name of each cow. I thought, "wow, how wonderful it is to be in a place where the animals who sustain us have names and not numbers." That's how it is to be with Baiano. Everything becomes personal.

It felt wonderful to be back sharing simple things like milk and coffee with him and Maria.

Somehow, Baiano's trademark hat seems like an icon of a well-lived life.