ANTIDOTE FOR THE WEIRD WILD WORLD

After a week of news of weird weather and wild wars, six year old skate boarder Asher Bradshaw shows how wild energy can be full of grace and joy.

The Venice Beach skatepark has this live-feed video stream. When the news gets too weird check it out for a few minutes and enjoy.

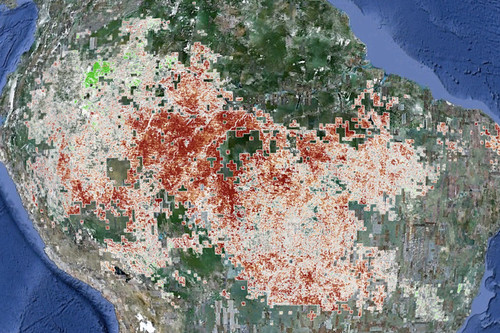

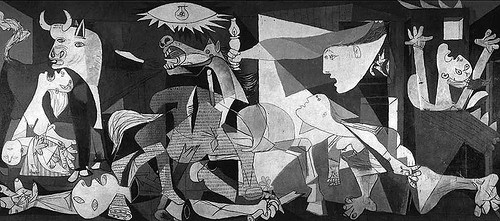

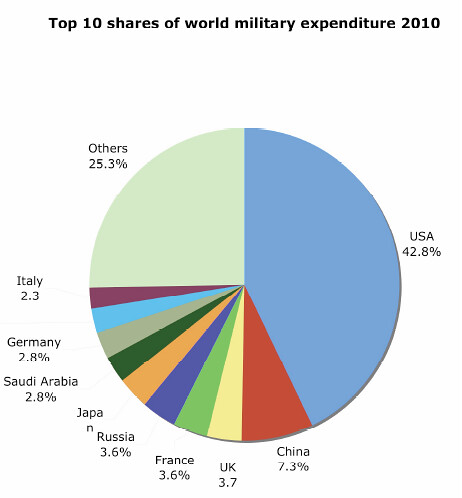

And please offer a prayer for those who are not so lucky.