[Editor's Note: Yep, I'm getting younger but I'm not yet into bike-riding. For sure, I'm always fishing for stories, especially ones that convey the flavor of Acre This one was written last December by Foster Brown who conducts research and teaches about sustainability issues at the Federal University of Acre. He graciously contributed this story and accompanying photos for publication in VisionShare.]

Getting younger, riding a bicycle

17 December 2008

by Foster Brown

José Cruz Neto is a 86-year old former rubber tapper from Brasiléia, Acre who gets on his bike and travels 120 km (72 miles) round trip to visit friends for lunch. During our last visit he mentioned that his goal in August 2008 was to go to Ibéria, Peru, 60 km beyond Assis Brasil, which in itself would be a 110 km jaunt, one-way.

These last few months, I hadn't been able to stop by Seu José's general store, so only on 17 December 2008 was I able to catch up on his travels.

As usual, I had set out with a simple goal in mind – hearing the story about his trip - and learned more than I imagined.

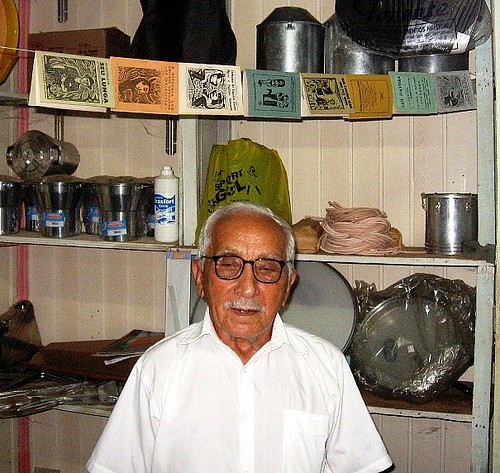

On a hot, bright 17 December in Brasileia, the cool and relatively dark Neto Cruz Store provided shade and balm for the eyes. In the back of the store sat Seu José, writing his accounts long-hand in ink. He recognized me immediately, and we began chatting about the current financial crisis ("I never believed using credit, so I have no debts; other shop-owners, however, are having serious problems”).

Seu José's general store

Before supermarkets and shopping centers became the temples of modern consumerism, there existed general stores where it was possible to buy just about anything, as long as you weren't too specific. Seu José has just a store - one room where it is possible to find propellers for a boat, pans for the kitchen, cloth for sewing, and literature suspended by a string.

The story of the Cruz Neto Store begins in the early 1940s. I had a chance to videotape his story and the following is a synopsis of what Seu José told me.

During World War II, Seu José was drafted from his home town in Ceará, a state in Brazil's impoverished northeast and given a choice: go to Europe or to become a rubber soldier in the Amazon. He chose the latter and ended up in Acre in 1943. He tapped rubber for two years until the end of the war and then had the choice during demobilization to return to Ceará or to stay in Acre. Seu José wanted to see more of Acre and became a policeman. Two years later he had an altercation with a colleague and was discharged from the police force. He noted that the colleague was later thrown out of the police and the captain asked Seu José to come back, but he refused.

Seu José began working for local commercial sellers, most of whom were either Sirio-Lebanese or Japanese. These local businessmen liked Seu José and would ask him to take care of their shops when they travelled. They encouraged him to become a shop-owner, but Seu José didn't have the capital at that time, so he started working on a boat, selling food-stuffs and buying rubber and animal pelts. After about two years he had had enough of being a river man and decided to run a store, something that he has been doing now for about 60 years.

A bookstore within a general store

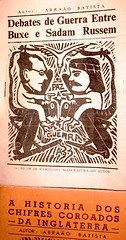

What I noticed first in Seu José's store was the Cordel Literature, appropriately stretched out along a string. These booklets have a long history, originating in Brazil's northeast and treat a variety of topics; typically they have a woodcut design for the title page.

The first title exhibits the phonetic spelling of someone hearing, rather than reading about the Iraq War: "War Debates between Buxe and Sadam Russem."

And then comes a common theme in Brazilian culture: sex, particularly adulterous sex. In Brazil and apparently in other countries, a cuckolded husband is said to be 'wearing a horn or horns'. The titles sound like a cross between self-help and true confessions: "The Cuckolding That Made Me Better"; "The Cuckold That Married the Other Man."

Seu José was a little nonplussed by the titles, but gave a shrug and said, well, that's Cordel Literature.

The general in general store

Two women entered the store, looking for a special type of kerosene lamp. Seu José lamented that he didn't have any left and added that they were probably not being manufactured anymore; the rural electrification program was making such lamps superfluous.

I asked Seu José if I could take a set of pictures of his store. He concurred and proceeded to tell me about his stocks. We were interrupted by two boys who entered looking for a pandeiro, a Brazilian tambourine typically used for Carnival music. Seu José had two types in stock, but the boys decided that they wanted a different style and left without buying.

Seu José continued with his tour. Besides the pandeiros, he sells guitars, propellers, and fuel containers. For those needing a drum, he has those for sale, too.

Along a central table he has pots, pans, water filters, as well as a squeezer for sugar cane. Crow bars, chains, and a vice complement the kitchenware.

Finally, along the east wall, Seu José keeps his bolts of fabric, next to the brooms

After the tour, we continued our discussion about the financial crisis. Seu Jose was sure that it will impact Brazil and affect his business, he didn't believe the pundits who considered that Brazil would be relatively immune.

Biking as medicine

My wife, Vera, had taken up bicycling recently, something that she had longed to do since her childhood. She knew of Seu José from the previous Innocence and wanted to meet him. I called her on my cell phone; she and Seu José then spoke about their passion for bicycling. For Seu José, bicycling is his health and the reason why he takes no medication, even at 86 years-old.

The trip to Ibéria

I then remembered why I had come to visit: to find out about his trip to Ibéria, Peru. Well, he admitted, he didn't make it to Ibéria. In previous trips to Assis Brasil, Seu José had made covered the 110 km in 6 to 6.5 hours. This time he took 7 hours, but he had a half-hour break for water. The hills to Assis Brasil are notorious, yet he went up them using a single-gear Caloi bicycle. He said he would stop going if he needed to walk his bike up the hills.

So why, then, didn't he go on to Ibéria, a mere 60 km away? Well, it had to do with the hassle of changing money. He had heard that in Iberia, Peruvians don't accept reals, the Brazilian currency, and he would have to buy some Peruvian soles beforehand. He wasn't sure how many soles he would need, and if he had extra then he would have to change them back into reals. All that effort didn't seem to be worth the trip to Iberia, so he and his partner decided to stop in Assis Brasil.

So, as usual, I went to talk with Seu José about one topic and left enriched with other perspectives. While general stores may be a vanishing breed, at least one is still in fine shape on the Brazilian-Bolivian border; now I know how to do one-stop shopping for a boat propeller and a guitar. Cordel literature stretched out on a string provides information in the western Amazon about the sexual adventures of British royalty. Medical prescriptions can be substituted with long-distance biking.

I didn't ask Seu José about his next trip, that will be the topic of another visit, but I'm sure that I will learn most about what I least expect, such as the debate between Bush and Hussein.

No comments:

Post a Comment