NUCLEAR ENERGY: TO BE OR NOT TO BE

Ten days ago, George Monbiot, the lead environmental journalist of the Guardian.UK, shook the tree of many environmentalists with a post that was provocatively titled, Why Fukushima made me stop worrying and love nuclear power. Of course, the reactions were fast and... "nuclear."

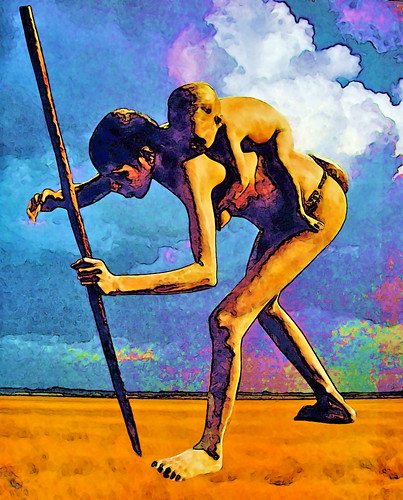

Now comes Monbiot's counterattack (re-posted below) which is well worth pondering. But before the re-post, I want to mention that some combination of solar, nuclear and wind power surely seems preferable to me than hydro development and gas and oil exploration across Amazonia. And, this thought is not just to save trees and forest peoples. Both locally and globally, even a heavy reliance on nukes would probably cause less harm than the currently planned projection of 146 dams across the Amazon basin.

The double standards of green anti-nuclear opponents

We must apply the same standards to all energy-generating technology as we do to nuclear power

The accusations have been so lurid that I had to read my article again to reassure myself that I hadn't written the things that so many of my correspondents say I wrote. So, before I begin the counter-attack, here's what I didn't say about nuclear power.

I did not claim that there is no alternative to atomic energy, or any such thing. Nor did I suggest that nuclear should replace renewables, or produce any higher proportion of our electricity than it does already. But I did point out that most of the countries that might abandon nuclear power are likely to replace it not with renewables but with fossil fuel, and that this is a major change for the worse. Environmentalist Mark Lynas has shown how phasing out planned nuclear programmes in a number of countries as a result of the Fukushima disaster could add another degree to global warming. Author and blogger Chris Goodall estimates that if the planned construction of new nuclear power stations in the UK stalls in response to the crisis, the result will be an increase of 9m tonnes of carbon dioxide for every year we delay.

Replacing the current generation of nuclear power stations when they reach the end of their lives is a tough decision. So is not replacing them. Not replacing them is a decision to do one of two things:

A. To switch to coal or gas, which means greatly increasing the rate of industrial deaths and injuries, levels of pollution and the impacts of climate change.

B. To add even more weight to the burden that must be carried by renewables.

Response A is far more likely, and appears to be taking place already: for example in Germany.

Like most environmentalists, I want renewables to replace fossil fuel, but I realise we make the task even harder if they are also to replace nuclear power.

I'm not saying, as many have claimed, that we should drop our concerns about economic growth, consumption, energy efficiency and the conservation of resources. Far from it. What I'm talking about is how we generate the electricity we will need. Given that, like most greens, I would like current transport and heating fuels to be replaced with low-carbon electricity, it's impossible to see, even with maximum possible energy savings, how the electricity supply can do anything other than grow. All the quantified studies I have seen, including those produced by environmental organisations, support this expectation. Ducking the challenge of how it should be produced is not an option.

Nor have I changed my politics (and nor for that matter am I an undercover cop, a mass murderer, a eugenicist or, as one marvellous email suggested, "the consort of the devil"). In fact it's surprising how little the politics of energy supply change with the mass-generation technology we choose. Whether or not there is a nuclear component, we are talking about large corporations building infrastructure, generating electricity and feeding it into the grid. My suspicion of big business and my belief that it needs to be held to account remain unchanged.

Nor is the Fukushima crisis anything other than horrible: dangerous, traumatic and disruptive. I'm urging perspective, not complacency.

OK, that's the record-setting done. Now for the counter-attack. Here is a list of what I believe are the double-standards that some of us who have opposed nuclear power (I include myself in this) have used when arguing against it.

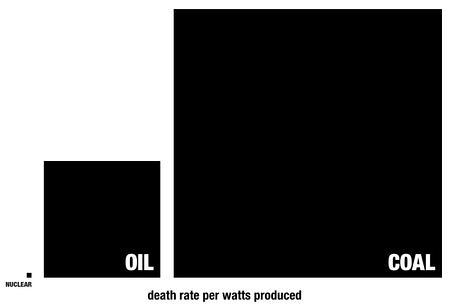

Double standard one: deaths and injuries

We rightly lament the horrible consequences of industrial exposure to radiation. Two workers at Fukushima have so far received radiation burns and 17 have been exposed to levels of radiation considered unsafe. This is and should be a cause for serious concern. It is also worth remembering that no one has yet received a dose of radiation that is known to be lethal as a result of the Fukushima disaster. But if we are concerned about industrial injuries, why do we say nothing about the deaths and injuries in the industry most likely to replace nuclear power?

In China alone, the government estimates that 2,433 people died in coal-mining accidents last year. That's not injuries or exposures. It's deaths. Human rights activists believe that official figures might have been underestimated by a factor of four.

What this means is that, in the normal course of operations, at least six people are killed in Chinese coal mines every day. Even if you accept the official figure, Chinese coal mining alone kills as many people every week as the worst nuclear power accident in history – the Chernobyl explosion – has done in 25 years.

And this is to say nothing of the far larger number of injuries that coal mining inflicts, in particular the hideous lung diseases which plague so many miners and cause long, lingering and terrible deaths. When was the last time you heard an anti-nuclear campaigner drawing attention to this daily carnage?

Double standard two: the science

We emphasise, when debating climate change, the importance of the scientific consensus, and reliance on solid, peer-reviewed studies. But as soon as we start discussing the dangers of low-level radiation, we abandon that and endorse the pseudo-scientific gibberish of a motley collection of cranks and quacks, who appear to have begun with the assumption that it must be killing thousands of people every year, and retrofitted the evidence to match it.

Such people exist in every field, especially those that are politically contentious. We should, by now, have learned to be wary of them. But it seems that the temptation, for people hoping to make the case against nuclear power, is overwhelming.

For a good summary of the scientific consensus on the effects of exposure to both high and low levels of radiation, see the new post by Chris Goodall and Mark Lynas: two environmentalists who have kept their heads in this crisis.

Double standard three: radioactive pollution

If low-level radiation really was the problem that some environmentalists say it is, the focus of their campaign should be coal plants, not nuclear power. As Scientific American notes:

"The fly ash emitted by a power plant – a by-product from burning coal for electricity – carries into the surrounding environment 100 times more radiation than a nuclear power plant producing the same amount of energy."This is because coal contains trace amounts of uranium and thorium, which are concentrated in the ash. Not only does this expose people living around coal plants to higher doses of radiation than people living around nuclear plants; but the regulations for disposing of fly ash are far weaker than the regulations for disposing of low-level nuclear waste. You may remember the controversy about RWE npower's plan to dump the fly ash from Didcot power station into a lake between the villages of Radley and Abingdon. Where were the anti-nuclear campaigners then? Can you imagine what the outcry would have been if a corporation had planned to fill it with low-level waste from a nuclear plant?

Double standard four: mining impact

Anti-nuclear campaigners emphasise the damage and pollution inflicted by uranium mines. They are right to do so. Some of these mines are hideous, and they are one of the many reasons why we should urgently develop new reactor technologies which sharply reduce the need for fresh supplies. But the impacts of coal mining are massively greater. There are hundreds of times more coal mines than uranium mines, including opencast sites, and a lot of them of them are many times bigger and more destructive than the largest uranium operations. This doesn't make uranium mining right, but it makes the likely switch to coal even more wrong.

Double standard five: costs

One of the most frequent arguments against nuclear power is that it costs too much. Many environmentalists claim that, when all the hidden costs, especially the massive decommissioning liabilities, are taken into account, electricity from atomic plants could cost as much as 5p per kilowatt hour or even more. The highest figure I have come across was the top end of the range of estimates produced by the New Economics Foundation – 8.3p. If this is correct – and I should emphasise that it's an extreme outlier – it suggests that nuclear is an extravagant means of generating low-carbon electricity.

So why do the same people support a feed-in tariff scheme under which we pay 41p per kilowatt hour for rooftop solar electricity?

Double standard six: research

Last week I argued about these issues with Caroline Lucas. She is one of my heroes, and the best thing to have happened to parliament since time immemorial. But this doesn't mean that she can't be wildly illogical when she chooses. When I raised the issue of the feed-in tariff, she pointed out that the difference between subsidising nuclear power and subsidising solar power is that nuclear is a mature technology and solar is not. In that case, I asked, would she support research into thorium reactors, which could provide a much safer and cheaper means of producing nuclear power? No, she told me, because thorium reactors are not a proven technology. Words fail me.

Double standard seven: timing

Anti-nuclear campaigners point out that it takes 10 years or so to build a new nuclear power station, and we haven't got that long, if we are serious about preventing climate breakdown. They are of course quite right: it's too little, too late. But the same problem affects every significant move to decarbonise the energy supply. By the time it has gone through the planning process, a major new grid connection to support an offshore windfarm will take roughly as long to develop as a new nuclear power station. The same goes for the pumped storage facilities required to support a largely renewable power system and for the carbon capture and storage required to reduce the impacts of fossil fuels. As for growing trees …

My point is that we have to take responsibility for every component of our energy supply and the consequences it carries; not just the section of it that's produced by nuclear reactors. And we should apply the same standards to all generating technologies. Otherwise, in the name of reducing risks to people and the planet, we will unwittingly increase them.

www.monbiot.com