WHY BELO MONTE (AND AMAZON DEFORESTATION) MATTER IN THE BIG PICTURE

The Amazon Basin is being targeted for large hydroelectric projects. 60 dams are planned in Brazil,

and more in neighboring countries Columbia, Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia. See full map database.

Across the Amazon Basin the pressing question is whether much-desired energy, fuel and food production can be increased without triggering cultural or ecological devastation. The environment of Amazonia is not an "empty" wilderness. It is inhabited by forest-dependent local people and thousands of species that have maintained a long-term relationship with each other. This ecological balance of people, production and forests is vital to the whole world and is being challenged by modern forces of development.

[Note: This post was revised 10/06/11 from an earlier version.]

The greatest experiment is taking place in Brazil and the broadest measure of sustainability is whether deforestation increases or decreases.

Belo Monte surely is one of the great symbols of the dilemmas of development. But, first and foremost, the gigantic 11-17 billion dollar dam matters for the lives of the people and forests of the Xingu River. When we use terms like Avatar or Pandora or say that this is an "iconic struggle" it can suggest mere metaphorical or mythical meanings for the rest of the world. Peoples and places can become mere symbols for appealing to faraway audiences who may believe they themselves are living in separate and somehow insulated realities.

Nothing could be farther from the truth. The precedent being established for Amazônia in the Belo Monte struggle and, similarly, in the battle for a new national forest code in Brazil will determine the levels of new deforestation and whether the Amazon continues as a forest drawing down and storing carbon or is tipped toward a becoming carbon source. This has global consequences.

Belo Monte and the Forest Code struggles are brush strokes painting the vision of what kind of a 21st Century we will have on the planet. As we collectively face the challenges of climate change, seasonal patterns of rainfall and drought across many regions will be determined mostly by where the terrestrial carbon is stored and whether it released into the atmosphere.

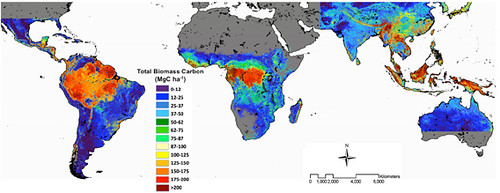

According to a recent study, here's where the forest carbon is stored

Click for large map.

Tropical forests across Latin America, Africa, and Southeast Asia stored 247 gigatons of carbon — more than 30 years' worth of current emissions from fossil fuels use — in the early 2000s, according to a comprehensive assessment of the world's carbon stocks.Think on it -- half of the world's forest carbon stock is in Latin America and a quarter is in Brazil, all of it based on resilient forests. Dams and roads lead to a huge influx of more settlers and/or agricultural expansion and thus lead to more deforestation, more fires, more emissions, longer droughts, less drawn-down carbon, and less released tree moisture (transpiration).

According to the study, forests in Latin America account for 49 percent of the total carbon stock, followed by forests of Southeast Asia (26 percent), and Africa (25 percent). Brazil's forests accounted for nearly a quarter of total biomass measured in the study. Democratic Republic of Congo (9.8 percent), Indonesia (9.3 percent), Peru (4.9 percent), and Colombia (4.1 percent) rounded out the top five countries, which together accounted for more than half (52.8 percent) of tropical forest.

The forests generate the minimum necessary rainfall during the dry season. As the sun's heat forces the trees to transpire, the Amazon forest pumps 20 billion metric tons of moisture into a "river in the sky" each day (compared with the17 billion metric tons of water dumped by the Amazon River into the ocean). The "river in the sky" determines the climate and the predictable rain and dry seasonal cycles. If there is not enough rain coming at the right time both agricultural and hydro-energy production will be diminished.

In the video below, the Brazilian climate scientist Antonio Donato Nobre describes how the "river in the sky" works. This perspective is only recently understood as the new data of global monitoring have combined with computer modeling technology to let us see what's going on in the air above us. It's an amazing story of a forest of 600 billion "geysers" determining global weather patterns. Please have a look.

[note: to see the English subtitles in the video, click on the red CC button at the lower right of the player frame.]

Brazil is at a crossroads of change. Will it follow the global model from the past, where short-term greed overwhelmed concerns for sustainability, or will it embrace new ways that honor limits and promote restoration and renewal? Writing about the struggle over a new Forest Code, Steve Schwartzman at the Environmental Defense Fund notes that many Brazilians oppose continued deforestation and support a new 21st Century vision of sustainability based on stopping deforestation.

Ten former environment minsters wrote, in a letter to President Dilma Rousseff,

"We understand… that history has reserved for our times… above all, the opportunity to lead a great collective effort for Brazil to proceed on its pathway as a nation that develops with social justice and environmental sustainability."This new vision of sustainable development is supported by a range of interests -- the scientific community, the National Council of Brazilian Bishops, the national association of attorneys, small farmers' organizations and environmentalists -- but it is butting up against traditional "conquistador" ways of past agricultural and energy expansion. In Brazil, many large agriculture, energy and mining interests still push for policies that produce more deforestation, demanding amnesty for past environmental crimes and release from requirements for establishing forest reserves as in the current battle over proposed Forest Code changes.

There are immense consequences of not having effective limits on deforestation. Look below at what happened as human activity expanded in the Amazon state of Rondonia during the most recent decade. On the ground, perhaps, each person saw themselves as just developing a farm or building a homestead or doing Brazilian business-as-usual in a giant forest that seemed infinite. But the cumulative impact was huge. Here are the NASA satellite images of the 2000-2009 land use changes wrought on a 500km wide area.

At the present "crossroads" the question is whether the above pattern of destruction will go on to new areas.

The mega-dams and the Brazilian Forest Code struggles present choices that have global consequences, they flag our planetary future. In the case of Belo Monte, dam construction will displace the people whose culture and lifestyle depend on the Xingu River and it will bring in a huge work force that will settle new areas. As the deforestation progresses, the "river in the sky" changes creating more extreme droughts and floods in distant regions and people far away from the Xingu will discover that their own cultures and lifestyles are also being unsettled.

Changes in one place create changes in other places, and that's how we are all related to these Amazonian struggles. Not merely in our hearts and minds, but also in our lives, the future of local people is our future. The climate is telling us that we are all connected and, in Brazil, the rate of deforestation is revealing how things are going.

No comments:

Post a Comment